The Centenary of the Ascension of ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá

Reflections on the Centenary of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Passing

Starting in November 2021, Bahá’ís the world over will observe the hundredth anniversary of the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the eldest Son of Bahá’u’lláh and Head of the Bahá’í Faith from 1892 to 1921.

As His Father’s successor, and the sole authorized interpreter of His teachings, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá led the expansion of the Bahá’í Faith from a largely Eastern religious movement into a global religious community spanning East and West. Bahá’ís revere Him as the perfect exemplar, in word and deed, of all Bahá’u’lláh taught.

This centenary year is an opportunity to reflect on His life and His contributions to the Bahá’í Faith and the cause of world peace.

A Life of Exile and Imprisonment

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was born Abbás Effendi, on May 23, 1844 in Tehran, Iran. In 1852, when He was eight years old, the Persian government exiled Bahá’u’lláh to Baghdad in the Ottoman Empire in an attempt to stamp out the new faith. At 12, the young Abbás was already managing the seemingly endless stream of visitors who sought out His Father.

After successive banishments to Constantinople and Edirne, Bahá’u’lláh’s family and fellow exiles were incarcerated in 1868 in ‘Akká, the penal colony of the Ottoman Empire, near Haifa in present-day Israel. The whole city was a prison, cut off by desert on one side and the sea on the other. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would remain in confinement for the next 40 years.

In spite of the family’s privations, He became known for His liberal charity among the poor, who would line up at His door every Friday. “He stations himself at a narrow angle of the street,” an observer wrote,

and motions to the people to come towards him. … As they come they hold their hands extended. In each open palm he places some small coins. He knows them all. He caresses them with his hand on the face, on the shoulders, on the head. 1

‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Canada

For Canadians, this year’s centenary holds a special meaning. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was released in 1908 when a revolution in the Ottoman Empire freed all political prisoners. In 1912 He travelled across North America for eight months, quickly becoming a recognized participant in the networks that shaped the international peace movement. They called him the Apostle of Peace.

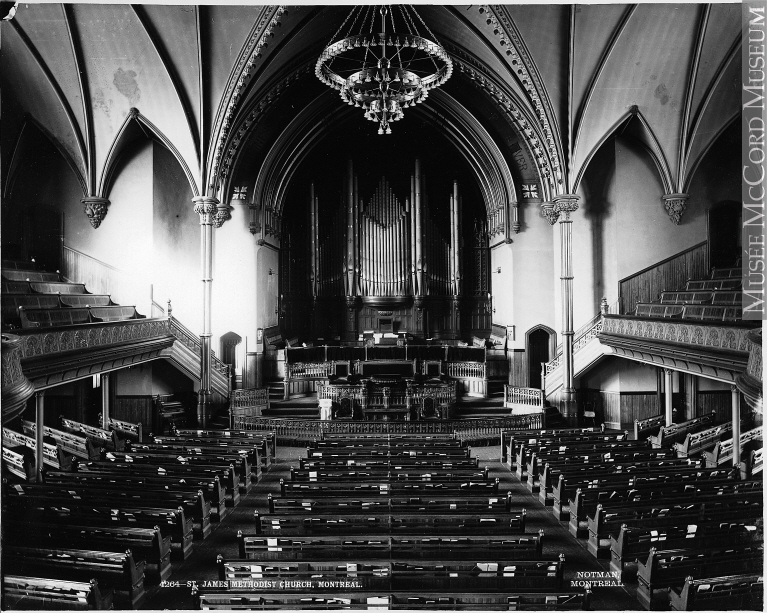

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spent ten days in Montréal, challenging Canadians with a vision of a world built on religious harmony, racial unity, the equality of the sexes, economic justice, and on new global institutions that would abolish war and secure a united global society. “May you become the cause of unity and agreement among the nations,” He said. A hundred years later, many of the principles and values ‘Abdu’l-Bahá promoted have come to be recognized as integral parts of Canadian identity.

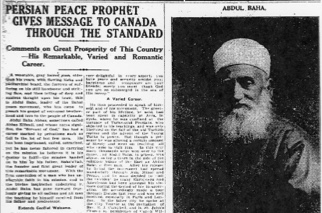

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s stay in Montréal was covered extensively by the Anglophone and Francophone press. A reporter for the Toronto Star recorded his impressions:

Picture to yourself a grey-haired man, older than his years, with patriarchal beard and face stamped by much suffering and serious thought, a yet handsome man, with a high, intelligent forehead and the idealistic eyes of a dreamer, a man of power, determination, too, who will tread one path when he knows that it is the right one, yea, though he should lose his life for so doing . . . . Put a white turban on his head and hang a gown of grey canvas over his stately shoulders. Then you will have Abdul Baha. 2

In His public remarks, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá expressed no illusions about the immediate prospects for the cause of peace He championed. “The continent of Europe,” He said,

is one vast arsenal, which only requires one spark at its foundations and the whole of Europe will become a wasted wilderness. . . . And what flimsy, what impudent pretexts they use. Patriotism, say they; glory, say they; the upbuilding of the continent, say they. What a travesty on God’s truth.” 3

War broke out in Europe eight months after His return to Haifa, but ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had already prepared for the worst. He had purchased farmland in the Galilee to grow wheat, storing the grain underground near Haifa. When a blockade threatened the region with starvation, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá fed northern Palestine: rich and poor, Muslims, Jews and Christians — a humanitarian act for which He accepted a knighthood from King George V.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá maintained a correspondence with hundreds of individuals, writing 20,000 letters to East and West. During the war years He sent fourteen landmark messages, directing the North American Bahá’ís to fan out across the world to teach their faith. And He left Canadians with a particular vision of our nation’s future promise. “The future of the Dominion of Canada,” He wrote, “is very great, and the events connected with it infinitely glorious. It shall become the object of the glance of providence, and shall show forth the bounties of the All-Glorious.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Legacy

‘Abdu’l-Bahá died on November 28, 1921 in Haifa. Ten thousand people attended His funeral. In His Will and Testament He laid out a system of local, national, and international elected bodies, and governing norms, to secure the unity of the Bahá’í Faith and direct its ongoing growth and community life.

A century later the Bahá’í Faith remains unique in having resisted the forces of division that have splintered the world’s major religions into denominations and sects. Bahá’ís now live in more than 100,000 localities worldwide and Bahá’í institutions have been established in more than 200 countries and territories. The first local Spiritual Assembly in Canada was formed in Montréal in 1922, and the National Spiritual Assembly was incorporated in 1948 by Act of Parliament.

Today, the principles ‘Abdu’l-Bahá advocated on religious unity, international peace, racial and economic justice, the equality of men and women, and dozens of other issues, have advanced to the forefront of most progressive movements. Bahá’ís worldwide come from more than 2000 national and ethnic groups.

It has now become clear that through the power of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s example — the leadership He provided, the writings He left, the plans He made, and the institutions He created — the growth of the Bahá’i Faith as a global religion, and its distinctive pattern of community life, are largely the result of His life and work.

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived in Montréal for His ten-day stay in 1912, only a handful of Bahá’ís could call Canada home. They lived in just a few in towns and villages spread across our vast nation. Without teachers, and lacking written texts, they had only a rudimentary understanding of their religion’s teachings. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit infused the scattered Bahá’ís with a sense of themselves as a community and a direction for the spread of their faith that would last a century.

“I have sown the seed,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told His listeners on His last day in Montréal. “You must water it.”

Footnotes

- This excerpt is from Myron Phelps, Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi, 1903. ↩

- Printed in the Toronto Star Weekly, 7 September 1912, quoted in Amín Egea, The Apostle of Peace: A Survey of References to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Western Press, 1871–1921, Vol. 1, 414. ↩

- From the Buffalo Courier, 11 September 1912. The full article is posted on the Bahá’í News Service. ↩